Innovation or repetition?

This week, I’ve been reading the new Post-16 Education and Skills White Paper. And on paper, it’s full of the right words: opportunity, excellence, levelling up, skills, innovation. In fact, “innovation” appears 35 times and “skills” 482 times. I am no mathematician, but in a 72-page document I think that averages about 6 or 7 times per page. Which is unfortunate given current youth vernacular (if you know, you know – and if you don’t – lucky you!). It is however unintentionally, quite apt. The white paper’s repeated invocation of skills works in much the same way as the 6/7 in joke – as a performative signal rather than a substantive concept. A kind of policy-speak catchphrase that gestures towards shared understanding without ever actually defining what it means, for whom or in what context.

Anyhow, I digress…..

The more I read, the more uneasy I felt. Not necessarily because of what was said, but because of what wasn’t.

The paper calls for two-thirds of young people to progress into higher education, but specifically in “priority areas.” That phrase says a lot. It quietly reinforces the idea that some types of knowledge, and by extension, some types of people, are more valuable than others.

Meanwhile, the leaders shaping these policies tend to share a familiar educational pedigree. Prime Ministers have historically come from independent schools and Russell Group universities, often with degrees in PPE (not that PPE – think Socrates not hi-vis) or Classics.

The authors of this paper, while state-educated, are themselves graduates in History and Politics. Respected disciplines, but hardly ones that would land them a job in the government’s own “priority sectors.”

None of these fields are “skills shortage” areas. Yet, somehow, they remain the route to influence and power.

So, when we tell working-class young people that their futures must align with government-defined “skills needs,” are we really widening opportunity? Or just re-drawing the boundaries of who gets to choose their future – who gets to dream?

If education for the privileged remains about cultivating the mind, while education for the rest becomes about filling skills shortages, then we’ve abandoned the idea of education as a public good. We’ve made it a sorting mechanism, deciding who gets to think and who gets to “do”. It reframes why young people should go on to higher education or training. It’s no longer education for exploration, curiosity, or cultural growth; it’s education as economic input, training as a labour pipeline.

And the proposed removal of the upper cap on tuition fees runs parallel to this, essentially saying:

“We want you to study more, but pay more for the privilege, and study what we tell you the economy needs, not what sets your soul alight.”

It’s a transactional model of education dressed in the language of opportunity.

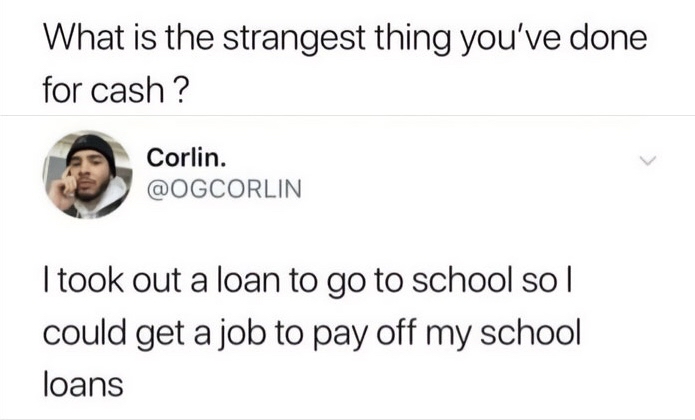

You’ve seen the meme for this one right?

Across the document, education has been quietly replaced by skills. Skills has, in turn, become shorthand for qualifications. These terms are used as though they are synonymous, as if holding a certificate automatically equates to being skilled. We know that’s not the case and it is why apprenticeships are so important – they develop skill sets as well as knowledge.

There’s a deep irony in a paper that celebrates innovation while recycling the same language of “skills gaps” and “productivity” we’ve heard for decades.

The focus on “priority areas” feels like a re-branding of the old “no more media studies” argument. The implication is clear: the arts, the humanities, the creative disciplines are indulgences reserved for the privileged. Those who can afford to learn for the love of learning continue to do so; those who can’t are offered functional training to fill workforce shortages …… and should be grateful for it?

Of course, employability matters. But shouldn’t working-class learners also have access to education that enriches, challenges and inspires? The things we still quietly call education when we talk about it for our own children?

The hierarchy of education

The White Paper also promises to hold FE colleges accountable for ensuring students have the same opportunities as those in sixth forms. Which appears admirable, but it overlooks a fundamental truth.

FE doesn’t restrict opportunity. The system does. And that distinction matters.

The reform focus is entirely on technical, vocational and adult learning routes, which implicitly positions A Levels as already “fit for purpose” – the gold standard that’s beyond scrutiny. As long as this remains the case, every new qualification, whether its T, V or X,Y,Z end up sitting lower down the ladder. When every new qualification still sits beneath A Levels in public esteem, we’re not expanding opportunity; we’re just rebranding inequality.

The V levels are presented as necessary because there is “too much choice” but the real issue is actually that the system doesn’t value all choices equally.

The Paper barely mentions A-Levels at all (only a handful of passing references, mostly comparative). That silence is meaningful. It signals that the academic route (the pathway traditionally taken by the privileged) is seen as stable, successful, and self-regulating. Meanwhile, all the “innovation”, “reform” and “skills investment” are aimed squarely at everyone else.

We’re still living with an education hierarchy that places A Levels at the top, vocational qualifications somewhere in the middle, and apprenticeships at the bottom, no matter how rigorous or meaningful they are. Which, if you look at it from a skills perspective, is completely topsy-turvy. That doesn’t come from within FE but from outside it.

It seems strange to say that we will be held accountable for a value judgment that has been imposed upon us — not created or perpetuated by us. To imply that the issue is one of ‘quality’ feels less like an honest diagnosis and more like an attempt to justify the hierarchy itself.

I see the effects of this every day. Brilliant, capable apprentices who build our roads, our infrastructure, and our communities, but whose qualifications and expertise still don’t carry the same cultural weight as those who took the “academic” route. The report even refers to these learners as Non-A-Level 😏.

I believe in skills. I believe in craft, in competence, in learning that connects knowledge to doing. Groundworkers, engineers, and care workers are not back-up plans, they are the foundations on which everything else stands.

If we’re serious about “levelling up”, then parity of esteem has to be more than a slogan.

The missing “why”

So yes, let’s drive up skills! Let’s set ambitious targets! But let’s also be honest about who defines what counts as success, and, importantly, who benefits from that definition.

There’s a telling section on the so-called “leaky pipeline”, where young people train in a priority area but don’t go on to work in it because the industry requires experience and work readiness as well as qualifications.

Apprenticeships would seem to be the obvious solution here, but instead, the paper positions T Levels as the answer, because of their built-in work experience requirement. Here’s the problem: there is no requirement for employers to pay students for that work experience. Some do, but it is more often than not offered as an internship.

For many working-class young people, working for free for ten weeks is simply not an option. A lot of my apprentices are relied upon to contribute to the household income. The wage isn’t an incentive, it’s survival.

To be clear these two ideas, the right to follow one’s ambitions and the need to earn a living, aren’t actually opposites. They only appear to be in a system that equates economic necessity with lack of aspiration. Levelling up shouldn’t mean having to choose between your dreams and your dinner…… right?

Perhaps the hardest thing to read was the section on disadvantage, which lists SEND, ESOL, and socio-economic barriers as statistics without ever questioning why they exist.

Disadvantage isn’t a learner trait; it’s a systemic outcome.

Eight pages in, my blood was boiling. By page thirty, I was tired. Not from the content, but from the constant sense that education policy has become an exercise in branding.

And let me be the one to say it, with all the references to AI in the paper — this report, reads as though it was written by a bot, not a person. Maybe too many politicians spoiled the broth? Or maybe the authors need to hone their prompt craft so that the output isn’t 72 pages of boilerplate phrasing and circular reinforcement.

A system repainted, not rebuilt

There is no space for learning for the love of learning, for broadening one’s mind, or for developing a sense of self here – that is not for us in FE. These things are protected and preserved for the privileged, the arts, humanities, literature, philosophy, while the working class are expected to be “job ready.”

If we can’t face that conversation, we’re not levelling up. We’re just repainting the same ladder. And we all know what the CSCS test says about that:

“Painting can conceal rot, decay, or other damage, making the structure unsafe.” 🤔

Leave a comment